Luke Scholl: The Rise of Writing (Chapter 4/Conclusion)

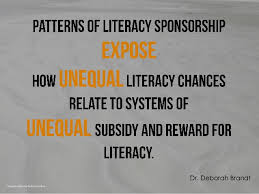

The fourth chapter of Brandt’s The Rise of Writing, “When Everybody Writes,” focuses on how writers and writing work in relation to other writers. As Brandt states, “Proximity to other writing people—ample, ongoing, routine proximity—plays myriad, formative roles in the development and calibration of writing, writing skill, and writing consciousness” (158). Early in the chapter Brandt discusses the “scenic” nature of writing (137-139). She notes that due to the fact that writing is scenic, that is something that takes place and can be witnessed, people are more acutely aware of how it works in the world. Brandt explains, “Seeing and being seen, knowing and being known—these everyday events form a broad undercarriage for awareness about how writing fits socially, politically, economically, aesthetically” (139). She then connects the scenic quality of writing to how writers interact with other writers. Because writing is scenic, writers are acutely aware of the writing that exists in the world: “Proximity to other writing people invites, and often requires, close attention to their habits, working conditions, and potential attitudes” (144). She also brings in the concept of mentalities and examines how it applies to her study of literacy. Brandt acknowledges how reading has historically disseminated information and thus contributed to establishing “shared understandings” (135), among the people of any given time and place within literate societies. However, she notes that as our literacy practices become more and more writing based, rather than reading based, the way we form these mentalities may be shifting.

In her concluding chapter, “Conclusion: Deep Writing,” Brandt co opts her nemesis Nicholas Carr’s phrase “deep reading” and reworks it to form her own concept of “deep writing” (159). She contends that the evidence provided her book suggests that we are “entering an era of deep writing” (Brandt 160). She argues that our literacy practices are no longer typified by prolonged and intense reading of texts but instead that “more and more people write for prolonged periods of time from inside deeply interactive networks and in immersive cognitive states” (Brandt 160). She ends her conclusion by examining the how these changes in our literacy practices present exception challenges for education as our schools are “growing increasingly out of step with the wider world” (Brandt 165).

During our discussion in class, Dr. Jaxon asked the students if we thought of each other and our professors as writers, and whether or not we really ever collaborate on writing or just give each other feedback. To me it seemed that the general consensus wound up being that we had not really seen at each other as writers until graduate school. This sentiment extended to our experiences with collaboration; I believe it was Kelsey King who stated, “the collaborative nature of writing is definitely something I’ve learned about through school.” I think when asked about our feelings toward collaboration in writing, many of our minds jumped to the concept of ‘group work.’ And like most sane individuals our knee jerk reaction to ‘group work’ is to say, “I hate group work.” I found it interesting that, for many of us, the concept of collaboration in writing was immediately conceived of as group assignments in school, and indeed our discussion did primarily revolve around collaborative writing within school. I couldn’t help but wonder how negative experiences with group work in school might contribute to the persistent stereotype of the solitary writer; even though, the form collaborative writing takes in these types of scenarios rarely reflects the level of professionalism, commitment, and responsibility that one might find when collaborating with a colleague in a professional environment.

I also find it interesting that the knee jerk, “I hate group work,” reaction has always seemed to be so pervasive. In my own experience I have been part of groups that were pure nightmares, but also groups that worked extremely well and which provided me with incredible amounts of support; yet, I still stand firmly in the “I hate group work” camp. I can’t help but think this attitude has something to do with the nature of school and grades. As students we are keenly aware that we are constantly being assessed. Despite that grades are just letters they failure to live up to a certain standard could, like writing, have significant and very real consequences in the world and their lives. The sociocultural significance and pressures of grades heavy influence the nature of group work in school. If you feel one person is not contributing enough you are angry that their lack of commitment will have an adverse effect on your grade, and, on the flip side, if someone is doing a large amount of the work you become concerned about whether you are contributing enough.