Matt Franks: Collins & Blot – “The Literacy Thesis” (A review of an old theory)

Collins & Blot – “The Literacy Thesis”

(A review of an old theory)

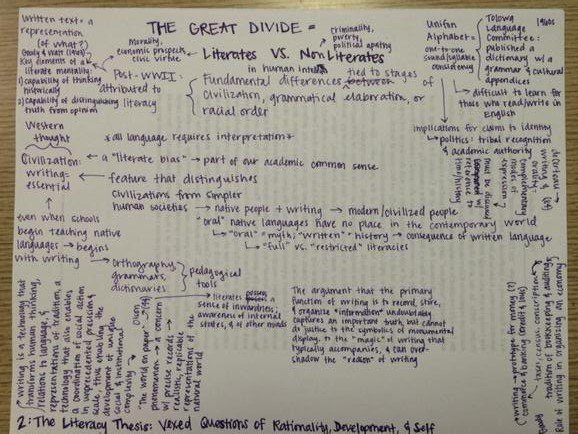

“The Great Divide” — Literacy, the ability to read and write, is purported to be the catalyst of cognitive, cultural, and social reformation into “modernity.”

On one side of this debate, literacy is seen as the defining aspect that allows for the construct and advancement of complex social structures, including economic and political. It is a dichotomy of literacy marking the line between the primitive and the civilized and has been the backbone of Western intellectual culture for a significant period, and still persists to this day to some degree. Collins and Blot point out that many of its claims range from incorrect to inconclusive, and this chapter takes many stabs at the insinuations of the argument that literate cultures are somehow inherently “better” than those maintained in oral tradition. The argument of literacy being the driving force of civilized society is somewhat more politically correct than the previous view: some people are simply, cognitively inferior. However, the question regarding the validity of these claims still remains.

On one side of this debate, literacy is seen as the defining aspect that allows for the construct and advancement of complex social structures, including economic and political. It is a dichotomy of literacy marking the line between the primitive and the civilized and has been the backbone of Western intellectual culture for a significant period, and still persists to this day to some degree. Collins and Blot point out that many of its claims range from incorrect to inconclusive, and this chapter takes many stabs at the insinuations of the argument that literate cultures are somehow inherently “better” than those maintained in oral tradition. The argument of literacy being the driving force of civilized society is somewhat more politically correct than the previous view: some people are simply, cognitively inferior. However, the question regarding the validity of these claims still remains.

Colonial powers forcing the adoption of language and written scripts is a real-world example of literacy used as a cultural weapon and part of a common theme placing literacy among the tools of power and domination. The ultimate goal was meant to change the mindset of target populations to a more European one politically, but also often religiously. That intended purpose was based off the assumption that literacy can act as a revolutionizing element of society on a fundamental level.

In contrast to forced adoption, one topic the authors bring up involves the preservation of disappearing languages, particularly those with no orthography. The goal is to leave a recorded format of the language for others to use in the contemporary world. The questions raised here are what is the “correct” way? and who is the effort for? The answers to these questions are significant in choosing the most appropriate writing system. In the presented case of the Tolowa, they chose a system against the wishes of linguists because not only did it perform well, but it did not look like English or a European script, something a native American tribe would likely find pleasing. This example situation speaks to the identity involved in written language and what significant changes may occur to a cultural identity during forced adoption.

In contrast with much of the previously mentioned notions of literacy as some sort of benevolent savior, the authors state that both Goody and Levi-Strauss emphasize the power of literacy asserting that it has a vast history of being used more for “enslavement than improvement” (19). Much of that domination is purported by Goody and others to be through economic, and religious functions. On religion, rituals are kept static, written and unaltered in time to control the actions of others from afar; this basically gives literacy the status of “epoch-defining” and depicts its relevance as drastically more significant than non-literacy. Collins and Blot take issue with this stance on the grounds that oral traditions are not fairly looked into in the same detailed manner as literate ones, and the issue is left inconclusive on those charges. In fact, most of the issues with Goody’s work in particular have to do with the lack of details on one side of the argument making it imbalanced.

Through the “literacy boosts cognition” issue comes another more troubling one, the connection between literacy and morality. The idea that those who could not read or write were somehow less virtuous, even criminal, sprung from the growing adoption of public education in North America and England.

Perhaps Olson’s main contribution to the debate was to say that having an alphabet led to a greater explicitness to language leading the reader to a more literal meaning. In this thinking, the understanding of that literal meaning is supposedly what allows the literate mind the capability of modern scientific thought: “logical, skeptical, and concerned with counterfactuals” (24). This would seem to state the contentious view that non-literate people cannot comprehend the literal; thus, Olson majorly revised the argument some years later softening its stance and allowing for a more nuanced appreciation for interpretation of meaning.

Some equations of non-literates to adults are made in reference to the ability to understand speakers’ intentions. The crux of the argument is that children cannot discern the difference until around the age of four to seven. Again, these are unfair characterizations as it is not said whether the adult subjects are not expressing the target behavior because it is not in their cultural traditions to do so. They certainly have the capability, and Olson eventually acknowledged that this is something we learn very early (29). Collins and Blot have less of an issue agreeing that certain literacy practices can help build a sense of self-reflection; the problem they have is overgeneralizing claims without substantial evidence.

After considering Collins and Blot’s presentation of the issue, many questions remain unchanged and in the end unanswered. Is a writing really as unalterable as some of the authors would suggest? Words can be written in stone but read in a different era with new context revising the meaning. This happens all the time, even with the knowledge of the original meaning. It would seem as if we use previous writings to fit our current purposes, not because we are unable to decipher them correctly, but because they are sometimes inconvenient to our modern sensitivities.

Or what about the effect literacy has on our cognition? Does it make us smarter? Better people? I can only think of a few readings that are likely to make one dumber… but “better people” is a completely subjective judgement call. I would imagine if some say being literate makes you a better person, then some would also say it makes you a worse person. One thing we can say is that there are documentable effects on our behavior related to literacy. So, is literacy the thing allowing us self-reflection without which we would be reduced to warring savages? I’m afraid we’ll have to find other reasons to blame for that.

Link to our notes for Collins & Blot