Travis Cowley: Curated Blog for Week 2

Hello all! This week we had two readings for the class. “The Social and Linguistic Turns in Studying Language and Literacy” by David Bloome and Judith Green, and the “Introduction” by Jennifer Rowsell and Kate Pahl from The Routledge Handbook of Literacy Studies.

Rowsell and Pahl’s Introduction to The Routledge Handbook of Literacy Studies first introduces the different complexities of literacy studies as a field of study. How literacy functions as a social platform to bring change, both in the context of communities and in the context of individuals. How literacy exists in every space of life: digital spaces, within material, rural or urban spaces, “across borders, languages and modes” (1). Roswell and Paul begin by describing the power dynamics surrounding literacy that try to inform what kinds of literacies matter and which kinds of literacies don’t matter. Roswell and Paul then begin to describe the research that continues to demonstrate how literacy studies as a field continues to expand beyond the limits it was originally put into. This continues to change the definition(s) of literacies– especially in the contexts that matter. The rest of the chapter breaks into different parts that describe different approaches or understandings of literacy studies.

Part I focuses on the different researchers (including Bloome and Green) who have laid the foundations for the ever-expanding branches of literacy studies. Part II is focused on spatial literacies or literacies that produce spaces that are “produced in societal contexts” (7), connecting literacy with community, society, and more global issues. Part III describes the literacy studies as a research that is longitudinal. This part of research focuses on the changes to literacy and literacy studies throughout time. Part IV focuses on how literacy studies can focus on literacies that are multimodal– existing across mediums, genres, and forms. Part V focuses on the turn in literacy studies into the digital world. Part VI looks at approaches to literacy studies that combine literary theory and hermeneutics. Part VII focuses on ‘functional’ literacy studies, which Tim Wall so aptly described, or uses of literacies in every day. Part VIII focuses on how research in literacy studies co-creates literacies that exist within communities. Phew! If that seemed like a mouthful or a list, that is because Roswell and Paul write this to give an idea that literacy studies are constantly changing, expanding, and adapting in different communities, fields of research, and in everyday life. This just creates definitions of literacies and different fields of research within literacy studies that are ever-expanding.

Green and Bloome’s article covers two different ‘turns’ or major changing points in the history of literacy studies. The first described is the ‘social turn’ in literacy studies. This is seen as a shift in the study of language as well. The best way I could describe this is in the difference between a prescriptive view of language from a descriptive view of language. Prescriptive views of language try to define language as it should be or could be in a kind of idealistic way. Descriptive views of language see language as constantly changing and thus believe there is no idealistic way of viewing language. The social term can be seen in the same light, where literacy studies switched from thinking of ways in which literacy should be to a more descriptive or ‘observing’ way of understanding literacy studies.

The second turn in literacy studies is the ‘language’ turn of literacy studies. This describes the way language (and by extension literacy) is rooted in society and social organization and this understanding of language provides a lot of implications for literacy studies through ethnographies and in thinking about literacy studies in social power dynamics. This problematized the methodology of ethnographies where “the ethnographer writes culture, not finds culture”(9) or in other words, the ethnographer looks at language and culture from an outsider’s perspective. This also brought into perspective the ways in which literacy is understood as a technical or social skill. Complicating the way in which we think of literacies as important in “social context(s) and that is situated within a particular social system” (10). That is, literacies are only important to the particular contexts in that they are needed. There is no universal limit of literacy that can qualify some people as illiterate and others as literate.

In class, we covered many different topics, often starting with a question that led to a complicated and shifting conversation, coming up with insights and answers along the way. The class began with debriefing. Kim Jaxon, our professor, laid out a potential agenda for our class time. We also expressed the different experiences we’re having as grad students– the stresses and challenges.

Kim then asked us a question: “What do y’all get out of these introductory readings…what’s the range of what this field (literacy studies) is covering”?

Ben started the class discussion by saying that the way literacy studies continues to expand and diversify makes him think that anything isn’t a discipline until academics study it. This led to a conversation on Western views of thinking– how something has to be ‘official’ or studied to exist in the Western world. This led to a conversation on reification, and the appropriation of different traditional Mexican and Mexican-American foods and beverages to fit a market of consumers who wish to buy healthier to-go food. Alondra brought up the example of a ‘spa water’ recipe by a tik tok creator that was essentially a bastardization and plagiarization of agua frescas. Larissa also brought up the example of street tacos being renamed ‘health tacos’ as a similar example of this.

We then shifted the conversation towards thinking of literacy as it changes throughout spaces. This conversation was grounded in thinking about how literacy changed in our online education throughout the pandemic. We all expressed our grievances with Zoom learning: how engagement was terrible through the zoom platform and how difficult it was to learn in the same space day-to-day. Kim then introduced the thought that Zoom learning mostly mimicked the kind of learning that is done in the classroom. Essentially, the solution to teaching students online was to mimic the same learning that is done in class, but on Zoom. But Zoom as a platform essentially revolves around the same dynamic of teachers telling students what they need to learn. It’s recreating the classroom, digitally, but forgoing the online dynamics that weaken student engagement. Leading to a more lectured, and less engaging environment for learning.

This led to a discussion about the ways in which students and teachers have been ‘school’d’ or shaped into thinking about school and learning in traditional and restricted ways. Cassidy brought up her example of teaching and her students continuing to ask to use the bathroom. Hayden also expressed an example of students wanting to raise their hands instead of speaking up to share something in class. Brady expressed that high school was not preparatory for college and even was pervasive in the ways students think about college. We also discussed the ways in which students are taught to write ‘in general’ in most writing composition classes. We discussed how this is problematic because there is no writing ‘in general’– the writing and reading needs for students vary upon context. Brooke brought up an example of a forensics class she took where she was allowed to use her notes during the test. Brooke explained that note-taking in forensics is a real writing/reading need. She explained how the class she took is an example of the class teaching or reflecting the real-life literacy needs required for the actual field the class is intended to prepare students for.

At this point in the class, I asked the grad students around the table what advice they would give to me as I will one day teach a writing composition class as they are now. Much of the advice led to a discussion on the importance of being flexible with students. This involves creating assignments that are relevant to what students are interested in. It also means designing a space that demystifies the different ways new students coming straight from high school may think college functions. It’s about being conscious of the environment new students are immediately coming from– an environment that very much has them school’d (high school).

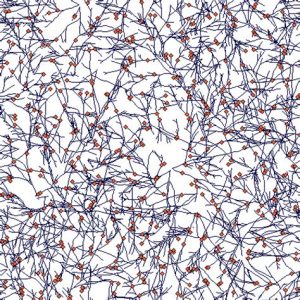

We then got to discussing the ‘social’ or ‘language’ turns in literacy. We spent some time defining and thinking about what those actual turns were. We discussed how literacy is really a moment in time. Trying to define literacy is like trying to map the exact form of particular sand dunes. They are always going to be sifting, shaping in and out of form like waves. We thought about the actual act of mapping literacies and literacy events. If we mapped literacy events in learning environments in time and space we think we would see something like a rhizomatic system. This led to Professor Jaxon showing us a video by Marijke Hecht that compared learning environments to rhizome root systems in trees. Professor Jaxon then provided us with papers and pens to map out our own literacy and learning events that have led us to where we are now. We weren’t able to finish this project during the class period and reflect on the experience, but I can reflect on my own experiences as I had them.

what those actual turns were. We discussed how literacy is really a moment in time. Trying to define literacy is like trying to map the exact form of particular sand dunes. They are always going to be sifting, shaping in and out of form like waves. We thought about the actual act of mapping literacies and literacy events. If we mapped literacy events in learning environments in time and space we think we would see something like a rhizomatic system. This led to Professor Jaxon showing us a video by Marijke Hecht that compared learning environments to rhizome root systems in trees. Professor Jaxon then provided us with papers and pens to map out our own literacy and learning events that have led us to where we are now. We weren’t able to finish this project during the class period and reflect on the experience, but I can reflect on my own experiences as I had them.

I felt like tracing my literacy and learning events was extremely difficult, and almost became too difficult of a project to complete within that class period. I started by thinking about why I was personally invested in reading and writing to begin with. A lot of my interest stemmed from my experiences with literature and how I believe developing a sense of critical thinking allowed me to think about my own life in re-inventive and productive ways. This laid the groundwork for much of my experiences with every course I’ve taken in college (which I mapped out) and every book I’ve read (which I also mapped out). ‘Thinking outside of myself is the direction the map was ultimately headed. It was connected to readings like Carmen Boullosa’s Before, or Yu Hua’s To Live, Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions, and Deborah Miranda’s Bad Indians. It was also connected to writers like Audre Lorde, Simone de Beauvoir, or Ibram X Kendi. The direction of ‘thinking outside of myself’ is also thinking ‘reflective to myself’– understanding the spatial, historical, and critical perspectives that are involved in reading, writing about and teaching literature as well as thinking about one’s own place in that field. The nodes became too many to connect on one sheet of paper for me. I decided to stop before I dug out too much of my brain. I hope as we continue this course we can continue to think about these questions:

-Why do we set standards for literacies? Who do these standards benefit? Who do these standards hurt?

-How can we picture environments of learning that are more rhizomatic? Or at least more inventive or creative than the standards of learning environments we continue to use?

-What kind of literacy events occur in our classrooms? Both the ones my cohorts teach and the class we’re in now?

-What kind of literacy experiences are we bringing to ENGL 632 with our unique backgrounds?

Author bio: Travis Cowley is an English Graduate student at CSU Chico. He’s doing the English MA program to develop professionally, research California Multicultural Literature, and because, believe it or not, it’s fun! If he’s not at school he’s probably at home gaming or hanging out with his lovely partner Bella.

Author bio: Travis Cowley is an English Graduate student at CSU Chico. He’s doing the English MA program to develop professionally, research California Multicultural Literature, and because, believe it or not, it’s fun! If he’s not at school he’s probably at home gaming or hanging out with his lovely partner Bella.