Hayden Wright: Curated Blog for Week 3

If someone asked you if the problem of literacy inequality should be solved, what would you say? At first, the answer to this question may seem obvious: of course it should! Why would anyone want to have literacy inequality? Well, that all depends on how the term “literacy inequality” is defined. Or rather, it depends on who is doing the defining, and why they are defining it that way, which points to a major problem with definitions. As we discovered from Rowsell & Pahl’s “Introduction to The Routledge Handbook of Literacy Studies” and Bloome & Green’s “The Social and Linguistic Turns in Studying Language and Literacy,” most literacy scholars can’t even agree on how to simply define literacy, let alone literacy inequality. So how do we know literacy is unequal if we can’t define it?

Once upon a time, literacy was understood simply as the skill of reading and writing. This skill, relatively new to human history, had radically changed the nature of how knowledge is constructed and stored: instead of relying on speech and memory alone, we were able to record language on a physical object that could be edited, read, and interpreted more easily than speech alone. With this skill came considerable power, something that the Catholic church saw as a major threat to their control of Europe when the printing press made literacy more widespread than ever. Once the common person was able to interpret the bible, question authority, and share knowledge with each other to organize their own ideas, it was pretty damn hard for any church to keep control over its followers, and a plethora of political, social, and spiritual revolutions followed. It seems reasonable, then, to infer that the skill of literacy is necessary for a society to advance, right? Surely everyone in the world should develop the skill of literacy, as it is a mark of functioning, intelligent, and conscious society. Literacy scholars like Jack Goody believe so. So does UNESCO. That’s why they want to get rid of “literacy inequality.”

Once upon a time, literacy was understood simply as the skill of reading and writing. This skill, relatively new to human history, had radically changed the nature of how knowledge is constructed and stored: instead of relying on speech and memory alone, we were able to record language on a physical object that could be edited, read, and interpreted more easily than speech alone. With this skill came considerable power, something that the Catholic church saw as a major threat to their control of Europe when the printing press made literacy more widespread than ever. Once the common person was able to interpret the bible, question authority, and share knowledge with each other to organize their own ideas, it was pretty damn hard for any church to keep control over its followers, and a plethora of political, social, and spiritual revolutions followed. It seems reasonable, then, to infer that the skill of literacy is necessary for a society to advance, right? Surely everyone in the world should develop the skill of literacy, as it is a mark of functioning, intelligent, and conscious society. Literacy scholars like Jack Goody believe so. So does UNESCO. That’s why they want to get rid of “literacy inequality.”

But now as our idea of what knowledge is expands more and more in each moment, we can’t rely on only one perspective of what defines literacy, especially if it was based on a technology that was created 600 years ago. And that’s the main problem with this perspective: it’s only one perspective, namely a white European male perspective—the “western” perspective, as it is so often referred to. Not everyone shares the same values as those from the western perspective, so shouldn’t we be taking into account the ways that other cultures and societies have dealt with collective knowledge? After all, most of them were doing just fine before the Europeans invaded their land, erased their knowledge, and manipulated them for profit. Surely, then, we must expand our definition of literacy in order to understand what makes it unequal for many societies.

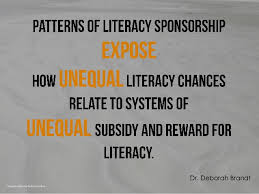

But there is power in a name, especially for those who do the naming. This point, along with the fact that the names of things have heavy consequences on the way policies for eliminating literacy inequalities are written and enforced, are things that literacy scholar Brian Street argues in his article “Literacy inequalities in theory and practice: The power to name and define.” In it he states that “not only is it crucial to know what we mean by [literacy inequalities] if we are to develop policy that actually works, but also because the very act of naming and defining is already an act of power, not just a separate academic exercise” (581), meaning that as long as our definition of literacy favors one culture and way of knowing over others, we cannot really call their idea of literacy as unequal. Goody’s definition of literacy is flawed because it tries to define but fails to describe, not taking into account the legitimacy of other cultures’ and societies’ literacies and value systems. According to Street, it’s an ethnocentric point of view: it puts one culture or society at the center of its understanding of how knowledge is constructed. In Street’s terms, this school of literacy studies is called the “autonomous” model of literacy because it “[uses] the power to disguise its own ideology, its own ethnocentrism” (581). To quote a male European man, “there’s the rub” of how literacy has been defined from the western perspective for so long.

Just like the way Galileo (who was, ironically, a European man) decentralized Earth from the solar system, Street wanted to decentralize the western perspective from its concept of literacy. He sees the problem with Goody’s definition of literacy and provides this solution: the ethnographic approach. He argues that if literacy scholars study literacy the way that ethnographers and anthropologists study culture, then perhaps they could get a more comprehensive grasp on what literacy can be. This led to a few changes in the way we understand what literacy is, one being the idea that literacy, like culture, “is a verb” (581); instead of defining literacy, we should be describing what it does. This leads to a shift from the concept of literacy as a skill, which implies it as a static, cognitive ability that only happens independently in an individual’s mind, to literacy events (which happen in a certain context) and literacy practices (which entail many processes) that happen socially. Street calls this new way of looking at literacy as the “ideological model” and, quoting himself, directly compares literacy to culture, remarking that “[t]he job of studying culture is not of finding and then accepting its definitions but of ‘discovering how and what definitions are made, under what circumstances and for what reasons’” (581). This would require literacy researchers to take the perspective of the cultures and communities of practice that they are studying in order to better understand what their literacy meant to them, and how they valued them. For this reason, Street preferred to describe them as plural literacies rather than a singular concept of literacy, all in the name of recognizing multiplicity in literacy that reflected the multiplicity in culture. To illustrate these points, Street uses a Buddhist story about fish and a turtle:

There was once a turtle who lived in a lake with a group of fish. One day the turtle went for a walk on dry land. He was away from the lake for a few weeks. When he returned he met some of the fish. The fish asked him, ‘‘Mister turtle, hello! How are you? We have not seen you for a few weeks. Where have you been?’’ The turtle said, ‘‘I was up on the land, I have been spending some time on dry land.’’ The fish were a little puzzled and they said, ‘‘Up on dry land? What are you talking about? What is this dry land? Is it wet?’’ The turtle said ‘‘No, it is not,’’ ‘‘Is it cool and refreshing?’’ ‘‘No it is not’’, ‘‘Does it have waves and ripples?’’ ‘‘No, it does not have waves and ripples.’’ ‘‘Can you swim in it?’’ ‘‘No you can’t’’ So the fish said, ‘‘it is not wet, it is not cool, there are no waves, you can’t swim in it. So this dry land of yours must be completely non-existent, just an imaginary thing, nothing real at all.’’ The turtle said, ‘‘That well may be so’’ and he left the fish and went for another walk on dry land. (584)

The fish are analogous to the autonomous model of literacy, who only know their own ethnocentric perspective of the world and cannot grasp the concept of dry land. The turtle—representative of the ethnographic approach—is only limited by his own vocabulary to describe what dry land is, and travels back to dry land to gain a better understanding through new terminology. Like the turtle, literacy scholars must take the perspective of the literacy communities that we are trying to describe in order to describe them.

| Autonomous | Ideological |

Enumerative induction

|

Analytic induction

|

| Ethnocentric | Ethnographic |

| Universalist | Relativist/particularist |

| Goody, Sen, Nussbaum, Unesco | Street, New Literacy Studies (NLS), Maddox |

| Sees literacy as a technical (and neutral) skill | Sees literacy as (social) practices |

| Believes in one central concept of Literacy | Believe in multiple literacies |

| Etic | Emic |

| Fish | Turtle |

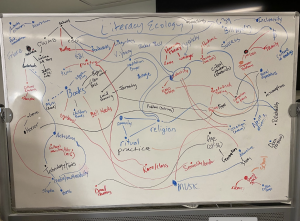

In the spirit of rhizomatic knowledge, I have decided to present the class discussion out of chronological order to group the in-class comments with the concepts brought to us by Brian Street’s article according to relatedness. But, since the act of writing alphabetic text is inherently linear, I naturally reorganized the comments and questions in a way that flows together but is achronological, accentuating the interconnectedness of the separate threads and digressions of our class discussion instead of the order in which the comments and questions were made. My repeated use of the word “point” is intentional: just as there were nodes that we created together as a class on the board to map out our literacies separated by space and time, the comments made and questions posed in class were particular points in time and space that made up micro-literacy events, connected yet happening separately and in an achronological order.

Our class session began with pizza, and I played the pizza man. As I brought the pie in, people were still trickling in. Kim told us to dig in just as class started officially.

Our task today was to map out our literacies on the whiteboard as a class. This was no easy task, as Travis stated so beautifully in his blog post last week: “Trying to define literacy is like trying to map the exact form of particular sand dunes. They are always going to be sifting, shaping in and out of form like waves.” Each of us in class were attempting to measure our own dunes, ever shifting from the winds of time, and then connect them to each other in a new context. It was messy. At an early point in the process, Kim suggested we write down the nodes first and draw lines for connection later, but that was soon thrown out of the window. No easy task, but it was fun!

There were many similarities between us, including books, language, identity, and a bunch of other wonderfully nerdy stuff, but also a lot of diversity between our influences, sponsors, hubs, and literacies. In reference to Street, Kim pointed out the importance of recognizing this diversity of literacies instead of focusing on whether students can perform a few select literacies that they get tested on in school. Then Alo brought up Street’s point about enumerative induction, and how we can’t reliably measure literacy with statistical data. Case studies are the way to go, it seems. But how do we go about it? Ben asked for clarification between etic and emic approaches to research at a later point in the class session, which I think highlights the main difference between autonomous and ideological models of literacy. The emic approach lends itself well to the ideological model that sees literacies as social practices, and the autonomous model seems to hold the belief that studying other cultures from an outside perspective can be objective. But on this same point, Ben raised another question: how can we really know if any outside perspective is truly objective? Don’t we all have biases? This made me think of linguistic prescriptivism vs. descriptivism, which Travis also brought up in his blog post. Like the way we use grammar, Travis suggested in class, literacies are flexible depending on the context in which they are practiced. Instead of prescribing parameters to literacy skills based on our own perspective, we should be trying to describe literacy practices based on the perspective of the culture that practices them.

In fact, Kim mentioned Dr. Judith Rodby and how she made it a point to never use the word skill to describe literacies, which implies finality—like they can be mastered and added to some type of cognitive toolbox. Instead, literacy scholars should refer to literacy events that happen at certain times and places, which make up the practices that go into a community. At an earlier point, Kim described literacy practices as value systems, to which Tim asked if we could gauge practice by various levels of participation. Of course we can! It was at this point that Kim mentioned Lave and Wenger’s concept of Legitimate Peripheral Participation (LPP), and I used my example of working at Laxson Auditorium. When I was first hired, everything seemed new and scary. They started me off with simple, inconsequential tasks, like tying on curtains to the pulley system. Eventually I was trusted with using the pulley system to take curtains in and out of the stage, which was moderately dangerous, and then finally I got to do the downright dangerous job of putting eleven-pound weights on the pulley system 60 feet in the air. Through LPP, I was able to build up the literacy events that culminated in the development of the practice of operating the curtain pulleys.

A large portion of the class was spent talking about the literacies of school. Just like how Travis continues the practice of politely raising his hand in order to participate in class discussion, there are certain practices and habits that schooling seems to do to us as we grow up. At an earlier point in our discussion that day, Alo had Tim write “Hand Turkeys” on the whiteboard to signify the Thanksgiving schooling practices that we all seemed to share. What does this literacy say about our experiences in the school system? It points to our personal identity, how we use our own hands to create art; it points to our national identity, how US holidays are celebrated and reinforced; and it points to colonialism, how we favor some perspectives over others that are suppressed and eventually lost. But when we are in Kindergarten making our little hand turkeys out of construction paper, safety scissors, and glue sticks, are we thinking about these things? No, but subconsciously we internalize these literacies, even if they aren’t always the most useful. At some point Kim brought up how Lave and Wenger refused to study the communities of practice at school for this reason. What’s the point of understanding school literacies if they only happen at school? There is a whole wide world of literacy practices that are more interesting and consequential to our society!

But school isn’t the only institution that ingrains us with peculiar literacies that affect the way we view the world. Ben pointed out early on that his experience in the Christian church had given him a lens through which he could interpret life, for better or worse. This reminded me of Kenneth Burke’s concept of terministic screens, which can be defined as a lexicon of specialized language that experts in a field make sense of the things they see. An artist would see a bird in terms of light, color, shadow, and dimension. A physicist would think of a bird’s flight in terms of gravity, thrust, inertia, and airspeed velocity. An ornithologist would know the bird’s Latin name, its habitat, its diet, its behavior. The problem that Kim points to is that sometimes our expertise in something can sometimes make us blind to what newcomers don’t know; sometimes the best writing students make the worst writing teachers because it’s hard to imagine not knowing what they know. I wonder what Chris Fosen’s term for this is?

At some point, Cassidy had asked a practical question: when assigning group work in a First Year Composition classroom, should students have the choice about which groups they are in? Kim generally seemed to value building community over choice in this regard, but it connected to a part of our conversation about student agency, a subject that I personally have much invested interest in. If students do their best work on things that interest them, how can we as educators provide them the freedom to choose their topics, while also fostering the specific literacies that go into academic writing? Kim mentioned “bounded inquiry” to describe the major project that she gave her students, and that led to wonder if there was some kind of balance, some sort of “controlled agency” that students could have in order to serve their identities and support them in their scholarly and professional pursuits. Travis pointed to an English class being taught at Butte College in which students voted on five books to read of their choice for the semester. But unfortunately, some teachers don’t have a choice. Larisa pointed out the fact that many high school teachers in the US start GoFundMe accounts to buy their students new and relevant books, increasing their level of choice and catering to their interests. Perhaps Street would see this as an issue with the connection between theory, policy, and practice.

At some point, Cassidy had asked a practical question: when assigning group work in a First Year Composition classroom, should students have the choice about which groups they are in? Kim generally seemed to value building community over choice in this regard, but it connected to a part of our conversation about student agency, a subject that I personally have much invested interest in. If students do their best work on things that interest them, how can we as educators provide them the freedom to choose their topics, while also fostering the specific literacies that go into academic writing? Kim mentioned “bounded inquiry” to describe the major project that she gave her students, and that led to wonder if there was some kind of balance, some sort of “controlled agency” that students could have in order to serve their identities and support them in their scholarly and professional pursuits. Travis pointed to an English class being taught at Butte College in which students voted on five books to read of their choice for the semester. But unfortunately, some teachers don’t have a choice. Larisa pointed out the fact that many high school teachers in the US start GoFundMe accounts to buy their students new and relevant books, increasing their level of choice and catering to their interests. Perhaps Street would see this as an issue with the connection between theory, policy, and practice.

On one end, there are the theories that scholars develop in order to understand how literacy practices are learned between members of a community, and on the other hand there are the actual communities where literacy practices are actually learned. Then there are the policies and policymakers in the middle, essentially acting as the middleman between theory and practice. But while policies are communicated and enforced in the name of improving education, they can actually be counteractive to the goals of the theorists whose ideas are used to make policy. Street makes this point in his article on literacy inequalities: while policy “works under the constraint of offering an overall and more uniform view of the issue at stake,” the theory that it is based on actually “complexifies the issue with multiple meanings and definitions and varied empirical examples” (583). Part of Kim’s teaching philosophy is to always combine theory and practice. Does that mean we should cut out the policy “middleman” to reach praxis?

- How do we reconcile the inherent opposition of the goals of theory and policy?

- How do we work Street’s ideas on the ideological model of literacy into our pedagogies?

- How do we put boundaries on literacies?

- And how can we truly be unbiased in our ethnographic approaches to literacy? Can we be either etic or emic in our research, or is it actually a spectrum?

Author Bio: Hayden Wright is an English Graduate student and first year composition instructor at California State University, Chico. His focus is in Language and Literacy and he is interested in learning and the creative process, writing his thesis project on interest and agency in the composition classroom. Hayden’s lifelong passion for music causes him to see the world in music-colored glasses, and occasionally you can find him wading in a body of water waving a fly rod at uninterested trout. His cat’s name is Quebert.

Author Bio: Hayden Wright is an English Graduate student and first year composition instructor at California State University, Chico. His focus is in Language and Literacy and he is interested in learning and the creative process, writing his thesis project on interest and agency in the composition classroom. Hayden’s lifelong passion for music causes him to see the world in music-colored glasses, and occasionally you can find him wading in a body of water waving a fly rod at uninterested trout. His cat’s name is Quebert.