Ibe Liebenberg: Brandt, The Rise of Writing, Chapter 2

In Brandt’s chapter two, “Writing for the State,” there is a clear connection made to chapter one’s idea of a ghostwriter’s inability to relinquish the emotional costs that are not deferred, or distributed with the transfer of work produced. One of the observations made in chapter two is that of an individual’s inability to write themselves out of work produced (86). This idea worked into our classroom discussion of whether to write ourselves into a paper or just get the job done for the grade, especially when there is no interest in the subject matter. It seemed like for most the public workers interviewed, they did not mind the writing in their field of expertise, so there was no lack of interest, but they felt it was too difficult to remove their voice. The contradiction of having a human write for the “state” or “government” but as a nonhuman element made it difficult for the workers to not use any of their own self. But the government knows how messy this can be: “Most intriguing is how government, including the courts, readily recognizes the intimate intermingling of the writer subjectivity with institutional mission as the dangerous mix that potentially undermines the government’s voice when employees speak out in the public domain and the political arena” (87). This intermix of human writing for a nonhuman entity will always have some form of human interference, but the government’s concern is to play a role to limit it.

We talked about how writing and teaching at the CSU level is constricting and limiting to both teachers and students. A student’s voice is rarely heard in a place where they feel that they are trying to appease the teacher. Likewise, professor’s feel the constraints of the administration. It raised the important question, do we have any reading without constraints? It seems like there is always some sort of filtering. We are almost always reading it for a reason other than our own. But constraints are sometimes good when thought of for something like creative writing. This is because it forces a form on the writer, or a lens to help write in. Where the opposite effect would seem to be limiting a creative writer, certain constraints actually apply parameters that allow the writer narrow their focus to just writing, instead of form or subject. Too much freedom can often result in a lack of focus.

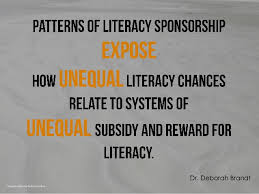

Chapter two also gave examples of how even the most scientific and self-removed writing can still be misinterpreted and skewed to fit the reader’s intentions, ultimately to influence an audience for someone else’s own agenda. This was the case with the writings of the scientist Melinda Lucas, who was a part of a complex thirty year “unbiased” study. She describes the complexities of her study and how everything she reports and deals with is just data. But when it is “rerepresented” (68) by media or other special interest groups, its interpretation is skewed by someone else’s agenda. In her case, a group wanted to use the data to save jobs, but we can see that even the most removed writing from the human bias can still be used and manipulated for others agendas and unprofessional interpretation.

The chapter finished with the idea that “There is no Occupational Safety and Health Administration for literacy” (87) to with help an individual writer who is writing for government in some form. Instead individuals like the police officer Henry Pine turned his writing into a means of releasing the emotional baggage by using his writing and record keeping as a way to transform daily experiences at his job into a journal to help export some of the psychological strain from himself to the actual report itself.