Brooke Kenney: Curated Blog for Week 5

Have you ever recommended a book for someone to read? Have you ever published or posted some aspect of your writing? Have you even re-tweeted a political opinion? Congratulations! You’re a literary sponsor. I know this seems like a huge responsibility and that’s exactly what our class discussed this week as we dove into Deborah Brandt’s “Sponsors of Literacy” and Bruno Latour’s “Third Source of Uncertainty: Objects too Have Agency” inspecting who counts as a literary sponsor, how the objects we use shape our experience with literature, and how sponsors use objects to their advantage (consciously or not).

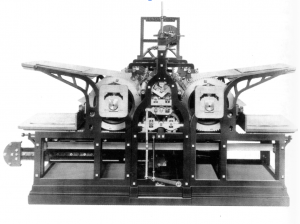

Let me rewind the tapes a bit so we can look at how sponsors began to evolve due to the ever advancing technology around us. Well, way back when, there was a great defeat of the printer as we know it. The mighty steam press came in and slaughtered the printer, wiggling its flag down and taking over the economy of the print industry. With the steam press came capital outlay and with that: the death of the independent press. This shift in working conditions moved to reflect literacy as a consumer product. While reading and writing were valued as a skill of expression and connection, it soon became valued for capital gain. So, this push in schools to obtain “basic literacy skills” is really a hidden agenda for getting a contribution to the economy. As the saying goes: Ask not what literacy can do for you, ask what you can do for literacy . . . or something like that. The steam press allowed for print to be made more accessible (because it made publishing more profitable) and therefore, the form of literacy sponsorship had been altered.

What is a literacy sponsor anyway? Brandt defines a literacy sponsor as “any agents, local or distant, concrete or abstract, who enable, support, teach, model, as well as recruit, regulate, suppress, or withhold literacy. . .” and this is the most important part, “. . . and gain advantage by it in some way,” (166). Brandt also has a great analogy to understand this by comparing sponsorship to TV. Just like how tv shows are sponsored by companies and corporations for their own benefit, so do sponsors of literacy. So, literacy became valued for monetary gain instead of helping society at large. This leads to Brandt’s second definition of sponsors as “delivery systems for the economies of literacy, the means by which these forces present themselves, to and through individual learners,” (167). Sponsors = delivery systems.

What is a literacy sponsor anyway? Brandt defines a literacy sponsor as “any agents, local or distant, concrete or abstract, who enable, support, teach, model, as well as recruit, regulate, suppress, or withhold literacy. . .” and this is the most important part, “. . . and gain advantage by it in some way,” (166). Brandt also has a great analogy to understand this by comparing sponsorship to TV. Just like how tv shows are sponsored by companies and corporations for their own benefit, so do sponsors of literacy. So, literacy became valued for monetary gain instead of helping society at large. This leads to Brandt’s second definition of sponsors as “delivery systems for the economies of literacy, the means by which these forces present themselves, to and through individual learners,” (167). Sponsors = delivery systems.

Brandt acknowledges and calls out these sponsors through her research on the “ordinary” American and their journey through reading and writing. The way we are taught to read and write shapes us as individuals and how we then in turn, become sponsors ourselves, even if it is just to your own child. The lengths people will go to “secure literacy for themselves or their children” really props up literacy as a tool of power, (169). This naturally creates competition, each individual fighting for a space in the world, a place to wiggle in their flag and declare their voice be heard for some sort of reason of gain. This kind of competition however, has shown the crucial need for access to the right kind of sponsors. Brandt looks at this through various case studies, one being the case of Raymond Branch and Dora Lopez. Both living in the same Illinois town, Raymond had copious amounts of sponsorship access with his dad being a professor while Dora had to fight tooth and nail to even keep hold of magazines to learn about her heritage. While Raymond had access to more evolved tools and more powerful sponsors, Dora was resource poor as an ethnic minority female even though they were in the same town at the same time. Their experience with literacy looked a lot different due to access to money and people. The main idea around this is that each individual’s literacy practices are functioning in different economies, which yield various degrees of sponsor powers and therefore, different monetary worth.

The effects of sponsors can be put simply:

- Facilitate access and opportunity to literacy

- Create competition for literary advantage

Brandt concludes on the idea that while we study individuals “in pursuit of literacy, we also recognize how literacy is in pursuit of them,” (183). So, the agency of sponsors plays a role in the given success of the learner.

But what else has agency? Latour argues that objects in fact, hold a lot of it. If you read Cassidy’s blog last week, you know this was a rather large debate in our classroom. We looked into Latour because Brandt and Clinton were using him as an example to paint literacy as a thing and show its “thingness.”

I’m going to use Latour’s definition of ANT (Actor Network Theory) that describes it as “an association between entities which are in no way recognizable as being social in the ordinary manner except during the brief moment when they are reshuffled together,” (65) but I do prefer Tim’s reference to The Big Lebowski that he used, “it’s like . . . all fluid man.” Humans and objects are fluid in the world together, one not being able to exist without the other.

Latour is reminding us that we would be nothing without objects and to not neglect their importance in our system of literacy practices and events. It is “always things. . . that lend their ‘steely’ quality to the hapless society,” (68). If objects are not actors in this space we live in then we would be able to solely act in society by the magical force of society alone. An example Latour uses is that “railings help keep kids from falling” meaning that if a kid is about to fall, they will grip the railing to stop that action. While we are the actors of agency, the objects around us are also actants of agency because without the railing, the kid would fall. We are reliant on objects as they are to us because they need us to use them in order to hold agency. This is a gray area where “there might exist many metaphysical shades between full causality, and sheer inexistence,” (72). So, ANT is not saying objects replace human actors but rather “no science of the social can even begin if the question of who and what participates in the action is not first of all thoroughly explored,” even if that means “letting elements in which . . . we would call non-humans,” (72). Ultimately, pay attention to the objects around you and appreciate them a bit more!

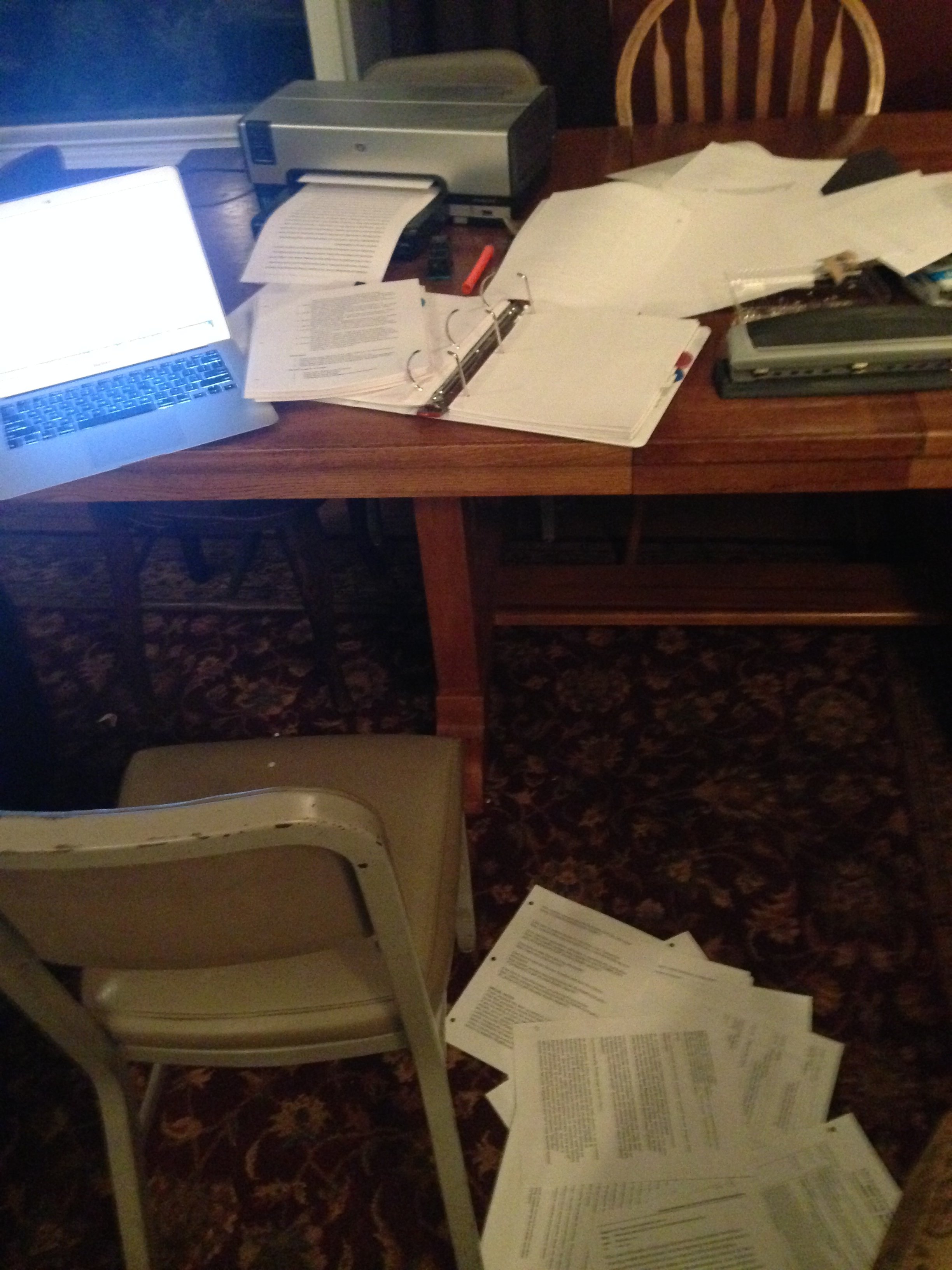

Sitting in chairs centered around six tables pushed together and eating pizza, our class discussion began. There was a heavy weight of defeat as the class surrendered to Latour’s argument on the importance of objects. Alondra brought up how when she gets home, she chooses a specific spot in her home to do homework at. The objects in the spot ultimately are the deciding factor for where she is to sit and focus on her work. Travis read aloud a poem “Shirt” by Robert Pinsky that traced back the origins of where the shirt came from, displaying the agency of the clothes you wear. Hayden brought up an idea from another class where the only information about animals that we know is from humans. We don’t actually know what it is like to be an animal and this idea helped him look at Latour’s argument. Kim brought up the fact that if objects didn’t matter then we wouldn’t care about what kind of classroom we were in.

Sitting in chairs centered around six tables pushed together and eating pizza, our class discussion began. There was a heavy weight of defeat as the class surrendered to Latour’s argument on the importance of objects. Alondra brought up how when she gets home, she chooses a specific spot in her home to do homework at. The objects in the spot ultimately are the deciding factor for where she is to sit and focus on her work. Travis read aloud a poem “Shirt” by Robert Pinsky that traced back the origins of where the shirt came from, displaying the agency of the clothes you wear. Hayden brought up an idea from another class where the only information about animals that we know is from humans. We don’t actually know what it is like to be an animal and this idea helped him look at Latour’s argument. Kim brought up the fact that if objects didn’t matter then we wouldn’t care about what kind of classroom we were in.

Of course funding plays a huge role in the learning environment one is in because the access to specific sponsors is a huge part in what we are able to accomplish in our classroom. Alondra asked for a definition of “social viability,” leading to a discussion on how sponsors are an asset to society and how we as students at this point in time are a sponsor for our english comprehension classes. Hayden mentioned the type of readings we supply to our students open up specific pathways but might disclude others. Cassidy mentioned how she is enforcing MLA in her class while acknowledging that there are other essay forms besides that one. Then, Ben came in with the question: Is there a thing of truly altruistic teaching? Is every sponsor actually benefiting somehow? How are we benefiting as teachers? What does a sponsor gain? Some of our answers:

- Experience

- Contributing to the economic exchange and getting a paycheck

- It feels good inside!

- Power and feeling smart

- ex) an older sibling watching their younger sibling play well in a soccer game and thinking “that’s all because of me! I taught him that!”

- Learning as a learner

- Tenure promotion

Hayden brought up an episode from “Friends” in which Phoebe and Joey discuss whether it is truly selfless to help someone else if you feel good afterwards.

We then talked about Literacy as an agency. “Having words to describe something is power,” Hayden mentioned. Travis asked if graffiti counted as having agency. Yes, the class decided. It has power and creates identity. It is performative and evokes emotion. Larissa’s friend brought up that in her art classes she is taught that when art is displayed it needs intent. With intent comes agency.

Then we split off into groups and shared our literacy interviews we conducted the previous week. I got to hear from Hayden and Travis, both with great examples of how literacy has affected the lives of their parents. Hayden interviewed his dad who when asked about literacy in his life, immediately referenced sports and how we would take down stats for the local highschool games and was offered a job for writing articles about sports. This was an identity for him: a sports writer. There was also an aspect of being sports literate. In baseball for example, each position has its own literacy. The pitcher is reading signs from the catcher and each player is viewing the game from a different perspective. Hayden then acknowledged watching his father write about sports probably influenced him subconsciously with the way he viewed writing (His dad and sports as a sponsor). Travis interviewed his mom and learned that his mother viewed literacy as a function after being taught to read signs on the road while on car rides with her father. She also saw how organized her mother was throughout her graduate school and noticed how she was “always making lists.” Handwriting was a big thing in her house from lists to letters and she admired her father’s handwriting especially and believed good handwriting to be important. Both the interviews picked up active sponsors in their life as well as objects being used to facilitate this learning. We can’t escape either of them! It truly is all fluid, I guess!

Here is an acrostic poem I wrote based off of Brandt’s “Sponsors of Literacies.”

Steam press began to

Pave the way for the

Only motives now

Nestled under literacies:

Self-advancement in the

Over-indulging economy. Gosh,

Read a book, would ya?

Here is a poem I wrote based off of Latour’s “Objects too Have Agency”

Ode to Pencil

Blood, sweat, tears

Displayed onto paper

Through your thin lines

Of lead. To lose you,

Would be to lose my thoughts

As fast as I can speak them.

You are what roots me

To paper, a way for me to stay

On this ever circling planet.

Some questions I have gathered from these readings and our class discussions:

- Does the definition of “agency” play a vital role in discussing its importance? Do all arguments that surround literacy ultimately come back to our definitions of it?

- How do we start ensuring equal access to sponsors in the early stages of literacy learning? (K-12 education)

- Do sponsors gain more out of literacy practices than the learners or is it an equal reciprocative relationship?

Author’s Bio: Brooke Kenney is a first year English Graduate student at California State University, Chico. Her focus is in creative writing and more specifically, poetry, where she writes about self identity and the effect traumas in life can have on the outlook of oneself. If she’s not writing, you’ll find her at her Barista job, meditating, or enjoying a nice mixed drink on her balcony. Just kidding! Probably just a beer.

Author’s Bio: Brooke Kenney is a first year English Graduate student at California State University, Chico. Her focus is in creative writing and more specifically, poetry, where she writes about self identity and the effect traumas in life can have on the outlook of oneself. If she’s not writing, you’ll find her at her Barista job, meditating, or enjoying a nice mixed drink on her balcony. Just kidding! Probably just a beer.